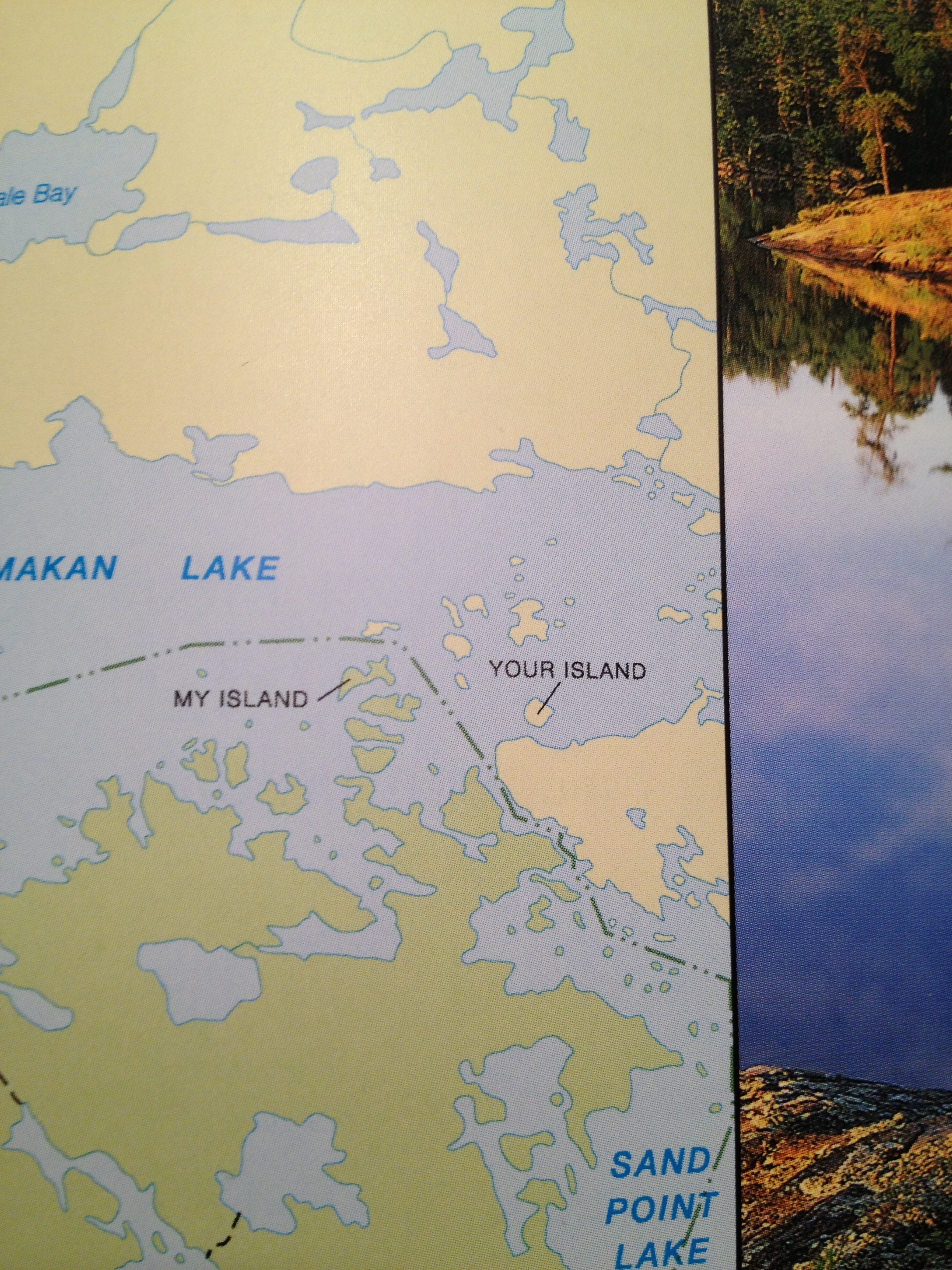

In an attempt to answer a somewhat random trivia question on National Parks the other day I found a book I received a few years ago. Flipping through, it’s a National Geographic coffee table book on America’s National Parks, and is chock full of amazing pictures and maps. My roommate and I were perusing and happened to stumble across these two curious and remote islands deep in Voyageurs National Park, located on the U.S./Canada border.

Many authors, academics, and cartographers have written about the idiosyncrasies and quirks in our maps, and even more have written about place names, geopolitics and their associated controversy, notably Mark Monmonier’s book “Drawing the Line: Tales of Maps and Cartocontroversy“, or Miles Harvey’s “The Island of Lost Maps – A True Story of Cartographic Crime“. Place naming and map design give cartographers immense power in defining place, and those designs and place names have fantastic story telling power and an incredible way of telling the history and character of a region.

What happened here? Why are these islands named this way? My Island is in the United States, Your Island is in Canada. Were two early voyageurs on this lake, one American and one Canadian (probably both French), standing on each island yelling and claiming things? The American was clearly dictating right? That’s why his island became “My Island” and the other became “Your Island”. But this is an American publication, right? What does this say about the time? Or the broader culture?

Maps take you on journeys without ever leaving your desk, office, bedroom, or couch. Much like music, actually. I find this to be incredibly well stated by Miles Harvey and the following specific excerpt from his book, “The Island of Lost Maps”.

“A map has no vocabulary, no lexicon of precise meanings. It communicates in lines, hues, tones, coded symbols, and empty space, much like music. Nor does a map has its own voice. It is many-tongued, a chorus reciting centuries of accumulated knowledge in echoed chants. A map provides no answers. It only suggests where to look: discover this, reexamine that, put one thing in relation to another, orient yourself, begin here… Sometimes a map speaks in terms of physical geography, but just as often it muses on the jagged terrain of the heart, the distant vistas of memory, or the fantastic landscapes of dreams.

I use a map to get from one place to another in my mind in the same way that someone else might use it get from Omaha to Oskaloosa. It’s a peculiar kind of travel, I admit, but I suspect many others embark on similar journeys”

-Miles Harvey, “The Island of Lost Maps”

What journeys have you gone on? Happy 2013!