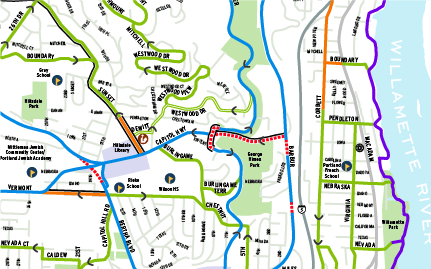

In a world of budding novice mapmakers and shares, likes, and retweets, we have never seen maps and graphics appear, circulate, and educate as much as they do right now. Maps are an engaging way to visualize data and gain knowledge. Geovisualization, cartography, and analysis are not only relevant, but highly visible to the mainstream, and it is great for the field. The New York Times and Washington Post, among many, lead the way with excellent, high quality, and reputable maps and graphics. We’ve all seen the forty maps that change your view of the world.

There is another side to this though, that of the mapmaker, specialist, or blogger that catches or creates a map, and in a whim of ‘This is cool!’ and with knowledge that they have a listening audience, relays the map into the internet universe. Little regard is sometimes taken in the validity or interpretation of the map and its data, or how it should be framed to the greater public. ‘Bad maps’, they could be called, are not new, but they now exist on an widely accessible mainstream level, and are fueled by Twitter retweets and Facebook shares.

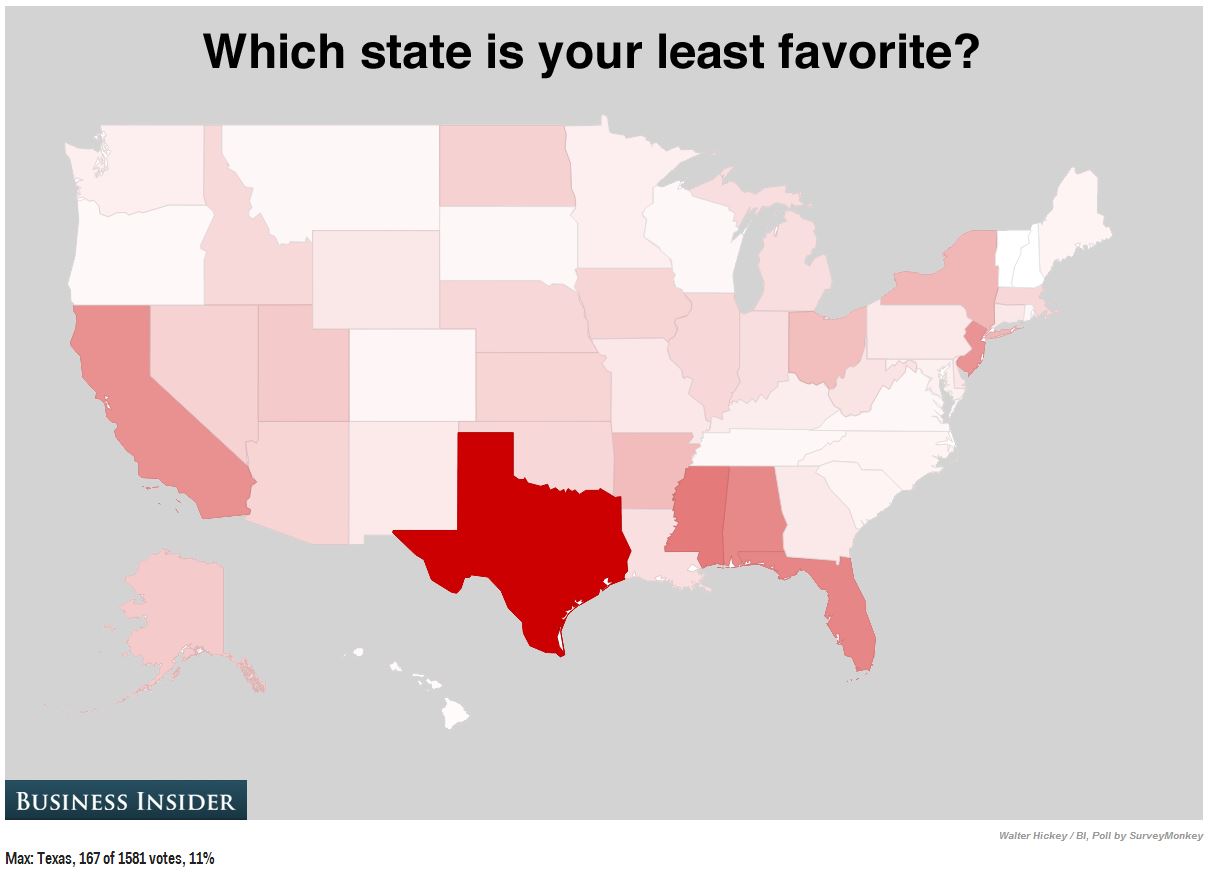

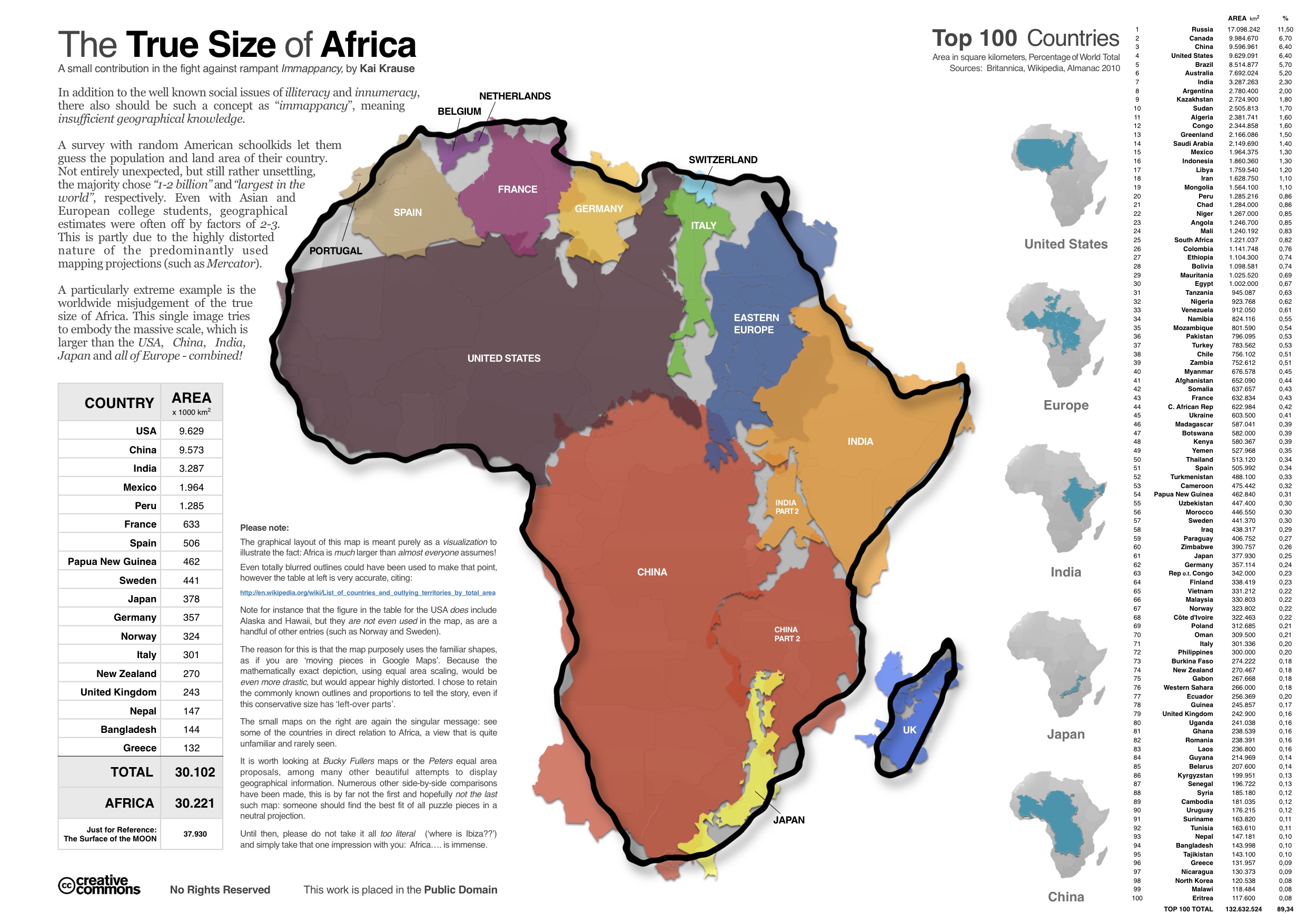

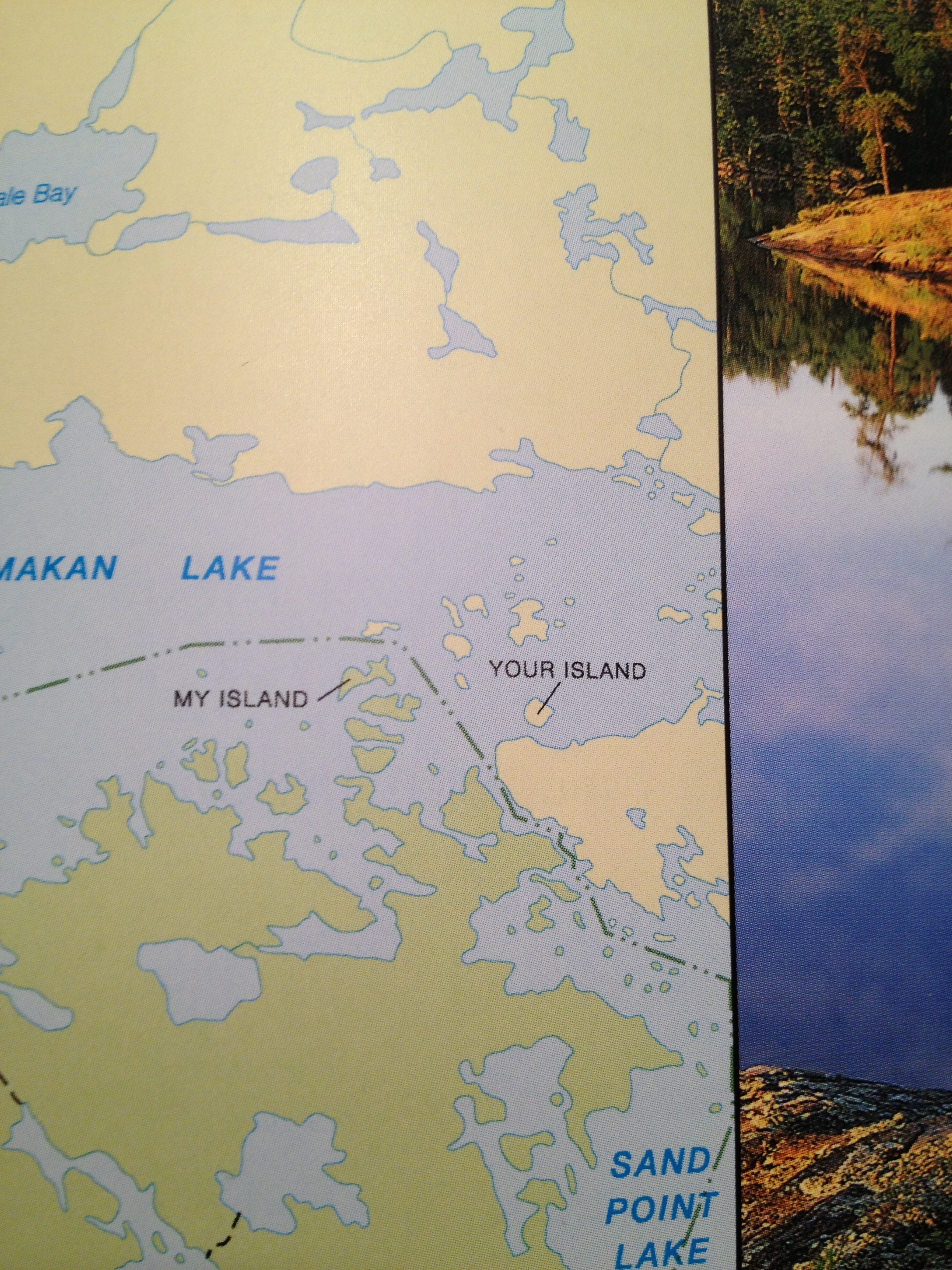

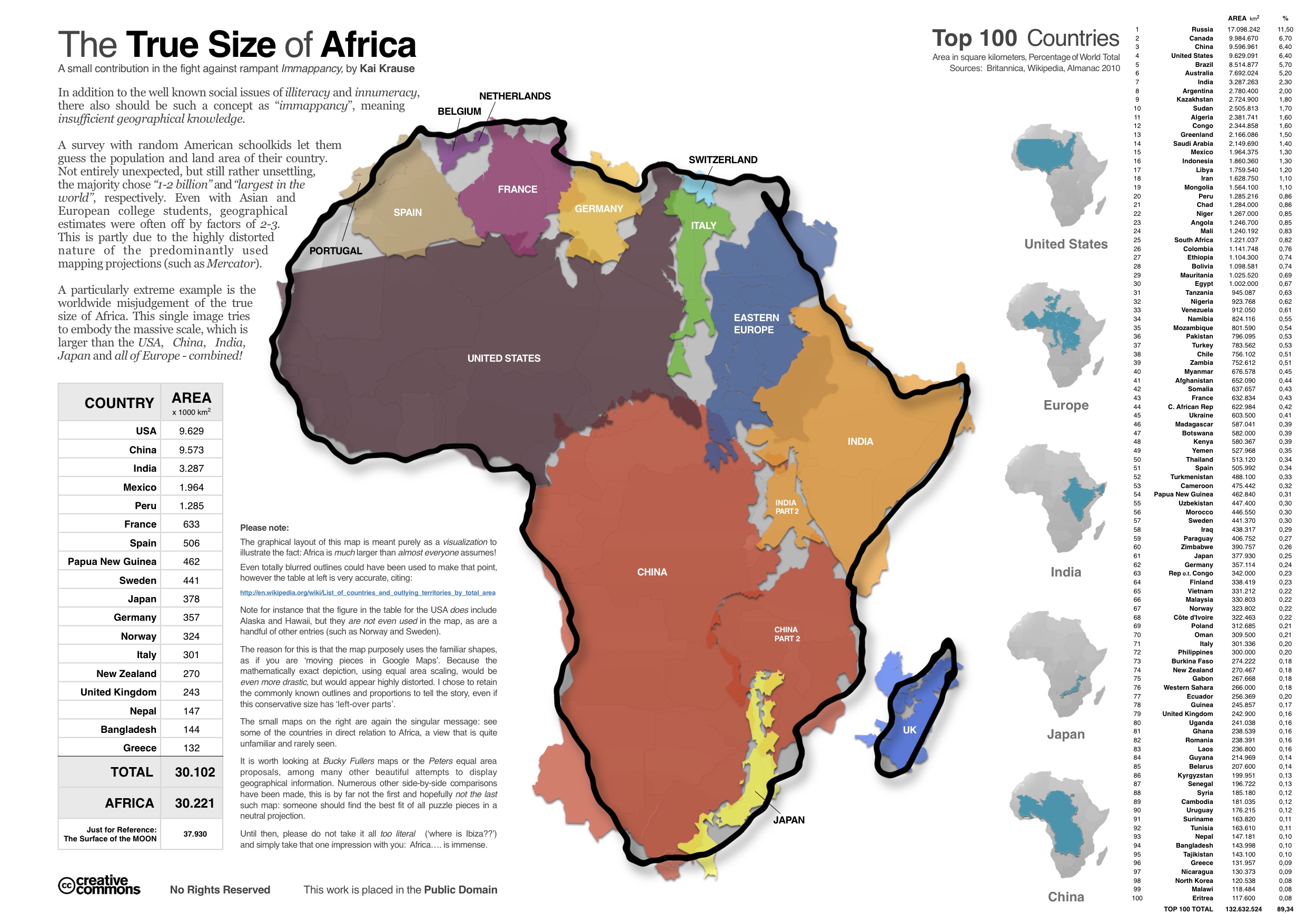

Obviously. (via Business Insider)

The ‘bad maps’ exist in multiple forms, starting with those that could be considered ugly (or graphically undesireable); those that might mislead readers; and then those that are just plain wrong. Maps that are simply ugly are not ‘bad maps’, per se. They communicate a message, convey a story, and serve to educate many. The quest to identify and improve these maps or even defend these maps, is emerging. Many talented and experienced cartographers and designers have initiated some great discussion on the topic, and poked plenty of fun at the issue. Virality of maps has become an important topic. Awareness of the issues will only improve cartography and data visualization in the long run.

That said, more troubling are the latter maps that are wrong or misleading, yet still gain the aforementioned viral steam and exposure. This discussion exposes a greater, more concerning problem that needs to be discussed – a pervasive lack of critical map reading skills.

Critical map reading takes the greater pedagogy of critical reading and applies it to maps and visual graphics. It is a form of map reading that does not take a map at face value, but instead examines the data, authors, sources, presentation, and prose of a map, investigating the claims those components assert. Maps are a unique medium in which every part of the composition is data. Given their inherent ability to relate specific topics to the earth we live on, maps are often viewed as truth and fact, and are rarely challenged. However, at the same time maps are storytellers, providing rich illustrations and the ability for interpretation. Cartographers mix these ingredients in a powerful and compelling manner, and many in the general public are largely blind to the concept that maps and visual graphics can be disputed.

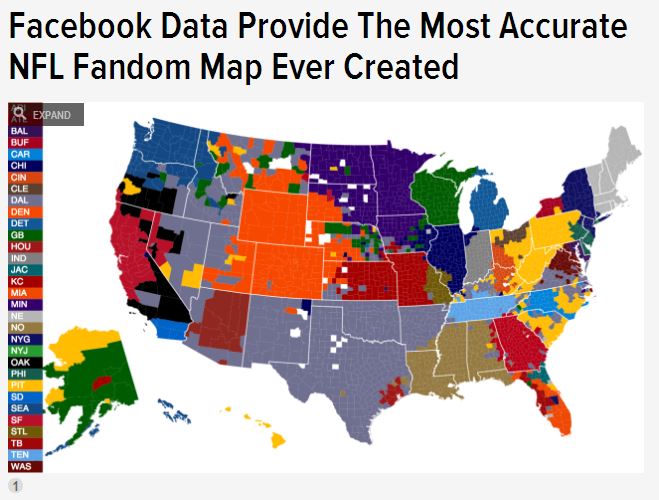

Part of the allure of a map is that it encourages the ability to interpret and explore. All maps contain a message, the practice of map reading is discerning and resolving that message. It is the questions that now become important. What makes this map “the most accurate”? Why is this map “incredible”? What methods where used on the data shown? Is a map the best way to show this data?

The route to critical map reading might not be clear, but awareness is perhaps the best place to start. Here are five simple habits that will improve map reading abilities.

Read all textual components and prose on the map carefully

Maps use both visual and textual communication methods. Even the most well designed map is nothing without context. Textual communication assists the reader in better understanding and interpreting the product. This content includes source information, titles, authors and affiliated organizations, and cartographic prose. Critical reading of this information will inform on how to properly intepret the product and relay it to others. Martin Elmer writes a well done piece on map prose here.

Note the ‘Please Note’. It will probably have a note that helps you understand the map. Or what the map isn’t.

Learn as much as possible about the data being shown on the map

Know the limitations of your data, and the constraints of the it’s graphical representation. Ask about the methods that acquired the data, and whether or not it has been summarized or simplifed in some form before being displayed. Data sources and original links can usually around the fringe of the map. Focus here on collection methods and manipulation tactics. Determine for yourself whether or not these are the best data sources to show the information, or whether or not the methods used are appropriate. Ask yourself, is the data qualitative or quantitative? Categorical or nominal?

This is not showing every state’s favorite band. The data and sources will expose this. (via MusicMachinery.com, Buzzfeed.com)

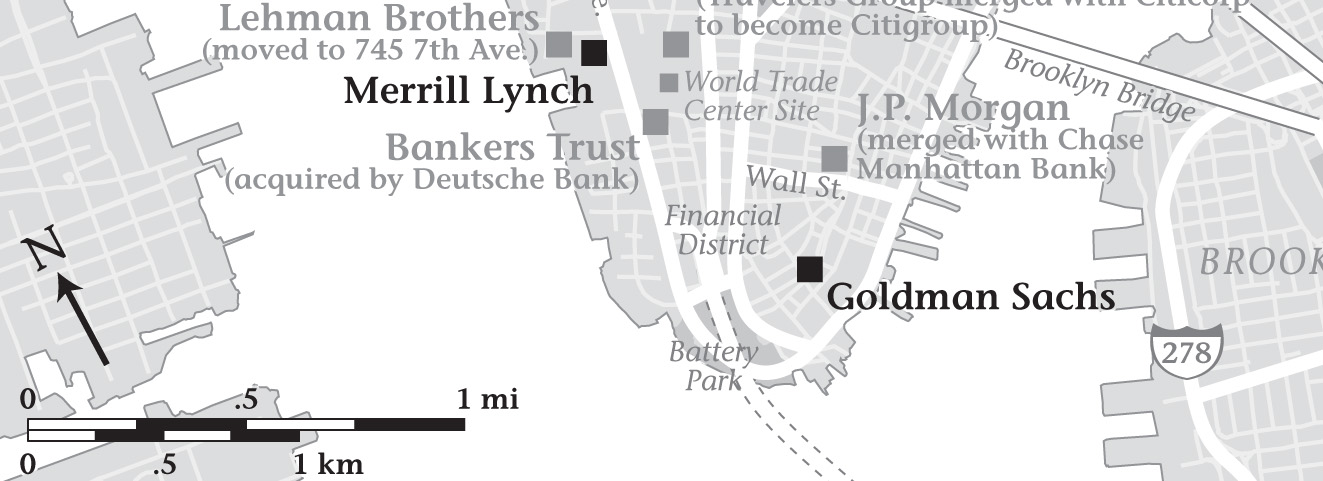

Note that everything on a map can be considered data

Falling close in line next, maps are unique in that not only the subject matter is data, the entire presentation can be considered data. A basemap of the United States is just as much ‘data’ as the points and colors scattered across it, along with the areal enumeration units. Sample case, some counties in California are the size of Massachusetts, yet national maps distilling information by county are common place. Consider how else the data could be shown, or what other options might be available.

I don’t think Romney won, but it looks like he did. (via SkeptimusPrime.com)

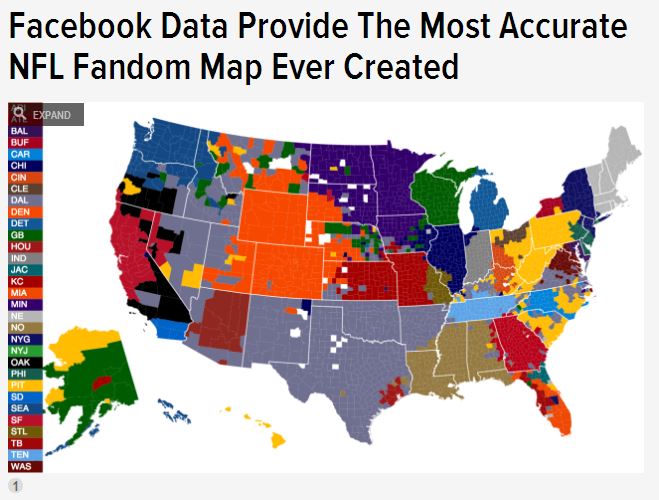

Be aware of what the map is NOT saying

Just as everything on a map can be considered data, critical map reading involves consideration of what is not shown on the map. Ask what data could be shown in complement with the data being displayed, or what additional variables or regions could be shown to improve the output of this map. Here lies the concept of ecological fallacy, in which information about individuals is deduced from the inference for the group to which they belong. Derive for yourself the strongest statements you can make from the data presented.

This might not represent ‘your’ favorite football team. This map isn’t wrong, its just also not necessarily… right. The Broncos sure are important though! (via Deadspin and CommonCensus)

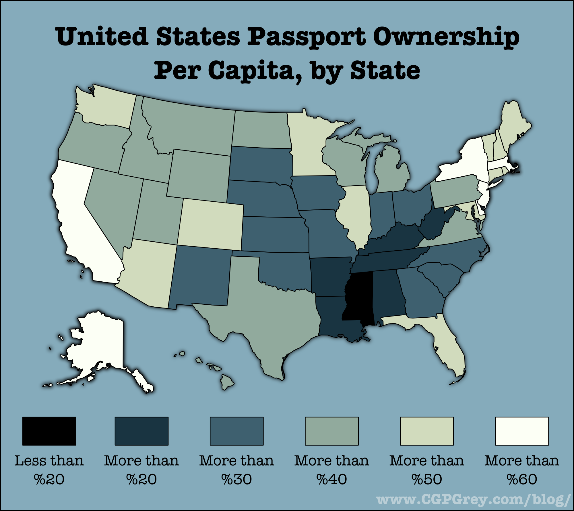

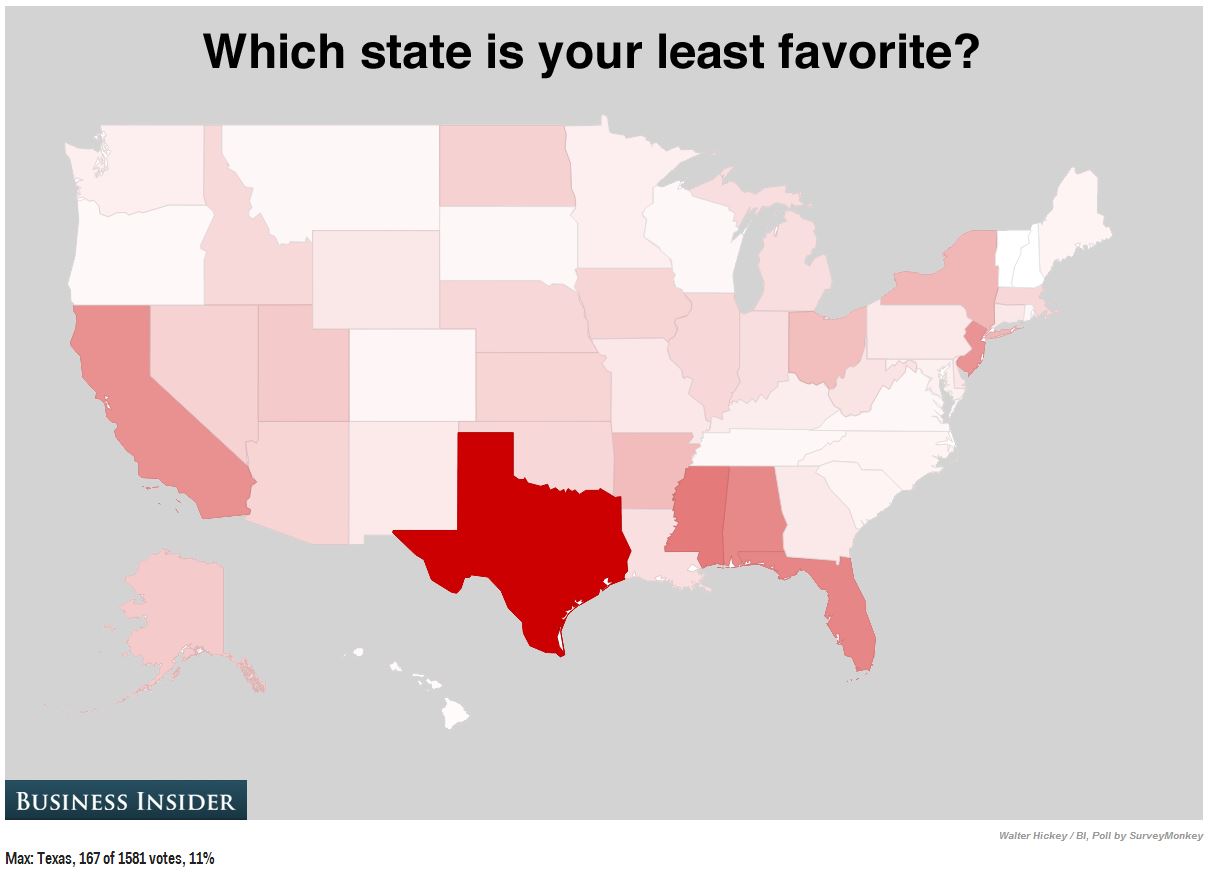

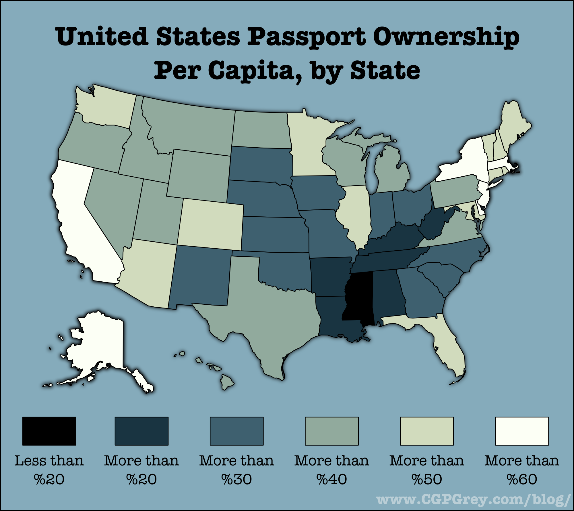

Notice that graphic representation and color encode bias and implied meaning

Maps visually communiate through a handful of variables. Perhaps the most quickly interpretable is the use of color and emphasize and exclamate points. Dark, bold colors imply importance, while washed out, desaturated colors imply the opposite. The chosen colors are a conscious (or unknowing) design decision made by the map author, and strongly affects reader interpretation. Envision changing the color scheme, or categorization method, and seeing how that affects the gravity of the map.

So Mississippi is the best? It’s the darkest. No, wait, is having a passport good or bad? What kind of color scheme is this? (via CPgrey.com)

Getting into these habits will help distill the the true message of the map, improve ability to gain knowledge from the map, and assist in interpreting a greater meaning about yourself and your surroundings. More reading abounds on this topic, and goes into much greater depth. Notably, Mark Monmonier’s How to Lie with Maps is perhaps the proverbial work on this topic, along with great reads by Denis Wood and Jeremy Crampton. Even the best designed maps require context and a critical eye.

In an era of information overload and retweets, critical thought of what is posted to and passes through our feeds is often overlooked. As maps and big data go mainstream, and visualizations become more prominent, educating map readers on critical interpretation becomes more important.

This is all almost as important as educating budding map makers on another thing… critical map making.

Like this:

Like Loading...